Watson made his political debut as a delegate to the Georgia convention of 1880. His impertinent opposition to the nomination of Bourbon Governor Alfred H. Colquitt, demonstrated in an extemporaneous but brilliant speech, immediately earned statewide recognition and branded Watson a political rebel. His opposition cast the convention into an impasse from which it did not recover and marked the first time Watson crossed swords with Patrick Walsh, skilled manipulator of the formidable Richmond County Catholic vote and Democratic editor of the Augusta Chronicle.

Stirred by the convention of 1880, Watson ran for the Georgia House in 1882. He was elected with notable support from black voters. At 26, Watson’s shrill voice and slight appearance in the Atlanta statehouse did not differ greatly from his mentor and newly elected Georgia governor, Alexander H. Stephens.v Watson’s early attempts at state lawmaking could only be described as frustrated opposition to the political rein of the Bourbon Triumvirate. To no avail, he opposed Colquitt’s seating in the U.S. Senate. Watson attacked the state convict lease system, which abused prisoners and profited corporations (and lined the pockets of Democratic Senator Joseph E. Brown), and sought relief for the conditions of tenant farmers. Watson’s attempts to increase the taxation on railroads were defeated, as were similar corporate reform efforts. Stymied, Watson resigned after his first session of the legislature downcast, presumably unmoved by glowing newspaper reports of his “brilliance” on the floor.

Although Tom Watson was formally out of the political limelight for almost the next decade, he was not detached from politics. He rallied local opposition against John B. Gordon’s gubernatorial bid, and in 1888 campaigned statewide for Grover Cleveland with fellow presidential elector John Temple Graves. During these years Watson increasingly bristled at Henry Grady’s promotion of an industrialized New South, and in frequent speeches debunked his vision as fundamentally at odds with the realities and interests of Georgia’s majority: the long-suffering farming class.

US House Chamber, 1890

In 1890, Watson was elected to Congress from Georgia’s “Bloody 10th” District. Although elected as a Democrat, Watson had campaigned on the principles of the Farmer’s Alliance that were soon incorporated into the Ocala Platform. His refusal to be cowed by his Bourbon counterparts attracted high praise from fellow Alliance supporters. “[He is] the most striking personality of the group,” wrote Hamlin Garland in the Populist Arena. “He speaks with a touch of the dialect of the South, and wears a soft hat in the Southern way. He is small and active. His face is perfectly beardless and quite thin. His eyes are his most remarkable feature, except possibly the abundance of dark red hair, pushed back from his face.”?

If newspapers and Democratic leaders demurred to his Alliance loyalties, they soon recoiled when Watson failed to support Charles F. Crisp–a Georgian—for Speaker of the House. Watson’s opposition to Crisp, who refused to stand on the Ocala demands, served as a rallying point for the Farmer’s Alliance and tempered permanently Watson’s position as a radical. Most Democrats, now threatened by the emerging People’s Party, branded Watson a demagogue and traitor to his party and the solid South.

Rural Free Delivery, c. 1910

If anything, Watson’s break with the Democratic Party galvanized his determination for reform. Except when ill, Watson attended every session of Congress and introduced legislation on most of the Ocala demands. In 1892, Watson introduced a bill to levy an income tax and one to abolish the customs duties on jute, jute bagging, iron ties, binding twine, and other materials used in cotton baling. Watson introduced a bill to abolish the National Bank, urged the free coinage of silver, pushed for a subtreasury system and advocated an eight-hour workday. Watson demanded the direct election of U.S. Senators. Also during his single session in the U.S. House, Watson proposed and secured funding for an amendment to the Post Office Appropriation Bill that would become the rural free delivery system of the U.S. Postal Service, earning Watson the sobriquet “Father of Rural Free Delivery.”

Watson’s titular claim that the populist movement was “Not a Revolt; It is a Revolution” was graphically supported throughout his failed 1892 reelection campaign against Augusta lawyer and Democrat J.C.C. Black. Watson’s successful challenge to Democratic rule and his advocacy for the political equality of the black farmer prompted violent confrontations between Democrats and Populists in towns across Georgia. Watson sparred with a supporter of Black in Thomson and was howled down in Augusta and Atlanta. In Augusta, several Populist supporters were killed; in Elbert County two black populists were shot on their way to the polls. Similar violence occurred in Dalton, Louisville and elsewhere. While visiting Macon, Populist presidential candidate James B. Weaver and his wife were egged. A black Populist campaigner for Watson, Henry Doyle, was nearly lynched in Thomson, prompting the armed protection of him and Watson by thousands of loyal local farmers. Tom Watson’s life was threatened repeatedly, and fisticuffs throughout the campaign were commonplace. In retrospect, Watson privately pondered it was “almost a miracle I was not killed in the campaign of 1892.”

While violence marred Georgia’s political process, it was manipulation and vote fraud that ultimately counted Watson out of Congress. Democrats gerrymandered Watson’s district prior to his reelection campaign. Bribery, ballot box stuffing, intimidation, voting by nonresidents and mass voting of blacks hired by the Democratic machine were tactics used throughout Watson’s district. In Augusta alone, where Federal agents proved helpless in their attempts to ensure proper polling, the vote against Watson totaled twice the total number of registered voters. Watson lost the election, despite carrying all the counties in his pre-gerrymandered district with the exception of Richmond.

Watson ran again two years later. The congressional election of 1894 was a repeat of the 1892 charade, but on a larger, more egregious scale. The economic plight of the farming class by 1894 was desperate; Watson’s venerated popularity in rural Georgia bordered on religious. Alarmed, the Democratic leadership bought votes with alcohol, intimidation, and cash. Populist ballots were destroyed. Watson again lost his election bid, though he carried nine counties in the district to his opponent’s two. Admitting the election fraud was notorious, some dismayed Augusta Democrats even complained publicly at seeing “worthless negroes vote dozens of times at ten cents each….”

Between 1894 and 1896, the Populist ranks swelled by the thousands across the South, largely because of defections from the national Democratic Party. Faced with eroding membership on the eve of a national election, the Democratic leadership desperately urged fusion between the two parties. Tom Watson, champion of the southern Populists and the intellectual leader of the national party, refused to equivocate and preached against any policy that sacrificed the fundamentals illustrated in the Ocala platform.

Watson accepts the 1896 Vice-Presidential candidacy.

Western Populists were more conciliatory. At their Chicago convention in 1896, the Democrats nominated William Jennings Bryan for president, Arthur Sewall for vice president and adopted a platform that included a demand for free silver. Tempted by populist planks and powerfully attracted to a Nebraskan they believed loyal to their cause, western Populists leaned towards fusing their own ticket with the Democrats. Watson balked at any such gesture and urged party independence. He reportedly refused Bryan’s offer of a cabinet post if Watson bowed out of the race. Tom Watson did not attend the Populist convention at St. Louis–an unfortunate and inexplicable mistake for the future of the party.

The chairman of the Democratic National Committee, James K. Jones, did attend the Populist convention. By working with western fusionists and against the southern radicals, he kept the former organized and the latter chaotic. At length, Bryan was nominated for president. When it appeared the southern Populists would bolt the convention in protest, Tom Watson was nominated as vice president with an assurance from the Democrats that his name would replace Arthur Sewall on their ticket. From Thomson, fearing the extinction of his own party, Watson reluctantly agreed to the compromise and accepted the nomination. The fused ticket appeared complete.

The deal proved a sham. In the Democratic circles the following morning, Chairman Jones denied having sacrificed Sewall for Watson. Jones was even more caustic days later, when he criticized the southern populist delegates as “not a credible class” and predicted their political demise: “They will go with the negroes, where they belong….” As Watson bitterly recalled, the moment proved “ …one of the most complete and deliberate deceptions that ever was practiced by one lot of politicians upon another.”

Despite the treachery that all but wrecked the aspirations of the People’s Party and a disingenuous running mate who refused to mount a stage with him, Watson campaigned admirably (if hopelessly) across the West in 1896. His efforts were futile. In the end, the Republican ticket of McKinley and Hobart headed to Washington. The Democrats retired to fight another day. The scattered Populists melted into the rural landscape, never again to organize as a viable third party. Watson, despondent over the Appomattox of his political life, returned home to ring the death knell for his party.

Watson ran for president on the People’s Party in 1904 and in 1908 as a protest candidate. Although hailed as “a beacon of light to those in doubt” by Clarence Darrow and other national figures, Watson did not seriously challenge his Republican or Democratic opposition. The passion and momentum of 1896 had largely subsided. In 1904 Watson earned barely 117,000 votes.

In 1910 Watson returned to the Democratic Party. Except for 1912, when he bolted the party to vote for Progressive Theodore Roosevelt, Watson remained within the Democratic Party for the rest of his life, albeit as a firebrand Jeffersonian Democrat and unwavering advocate of populist principles. Watson refused numerous entreaties for a gubernatorial bid, but his enormous statewide political influence ensured that no Georgia governor between 1906 and 1922 was elected without his express support.

In 1918 Watson was again urged by supporters to run for Congress. Despondent over the recent deaths of his two oldest children and frustrated by the effective silencing of his newspaper, Watson surprised many when he agreed to oppose Representative Carl Vinson. Watson’s platform, consistent with Jeffersonian philosophy, opposed the overseas war, involvement in the League of Nations, and virtually all policies of the Wilson administration. Vinson, on the other hand, was a popular patriot and war hawk. Although Watson entered the contest late and was in poor health, he ran a surprisingly close race. Vinson defeated Watson by two county unit votes. Watson’s protests of election fraud were ignored.

Watson came back in 1920, stunning his political opposition by beating U.S. Senate incumbent Hoke Smith and former Georgia Governor Hugh Dorsey. Watson took 110 counties and won the U.S. Senate seat without a runoff. After three decades of formal absence from national politics, Watson returned to Washington as Georgia’s freshman senator.

In 1921, Watson gave his final speech in Thomson, Georgia, and left Hickory Hill for Capitol Hill. As a U.S. Senator, Watson attended every assembly session in the 67th Congress. His battles, consistent with his Jeffersonian convictions, ranged from fighting America’s land purchases in support of oil exploration to advocating the diplomatic recognition of soviet Russia to crusading against America’s participation in the League of Nations. Watson urged the restoration of civil liberties for the political prisoners of Woodrow Wilson. Watson opposed militarism and denounced the imperial designs of the administration and its request for an increased standing army. Watson also forcefully opposed the attempted seating of millionaire Henry Ford in the Senate because of Ford’s notorious anti-Semitism.

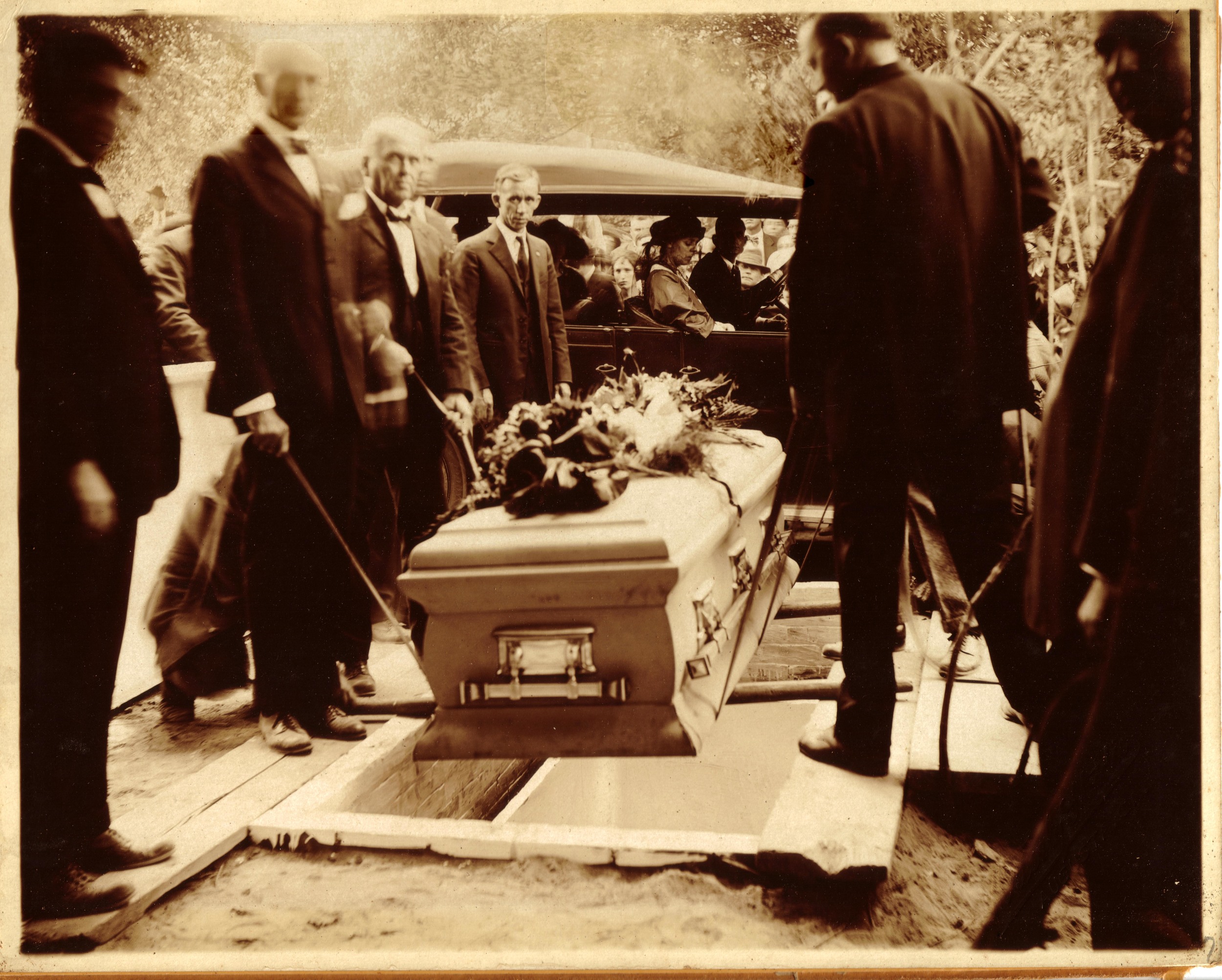

Despite having fallen seriously ill several weeks before, Watson insisted on attending and speaking on the final day of session, September 22, 1922. His precarious health continued to decline and on the night of September 25, suffering from chronic asthma, he was unable to rise from bed. Watson died of a cerebral hemorrhage on September 26, 1922 at his rented home in Chevy Chase, Maryland. Watson’s fiery assistant, Alice Lytle, remained in Maryland to handle the arrangements. Upon learning of the railway’s intention to place the Senator’s casket into a baggage car, Lytle protested: “The Senator did not arrive in Washington in a baggage car; he will not go home that way.” Watson’s body was returned to Thomson via a Pullman car.

It is estimated that 10,000 people attended Watson’s funeral at Hickory Hill. Georgia Watson died on May 14 the following year. The Watsons were buried with their children in the Thomson City Cemetery.

Watson died without realizing his lifelong dreams of sweeping Jeffersonian economic and political reforms and a political alliance between the South and the West. Many of his reform initiatives came to life posthumously, including:

• Graduated income tax

• Inheritance tax

• Government regulation of public communications and transportation

• Government ownership of public utilities

• Agriculture subsidies

• Recognition of the right of labor to organize for protection

• Abolition of child labor

• Eight hour work day

• Abolition of the convict lease system

• Initiative, referendum and recall

• Secret ballot system

• Direct elections of U.S. Senators