Cody–McGregor Case, Warrenton, Georgia, 1890

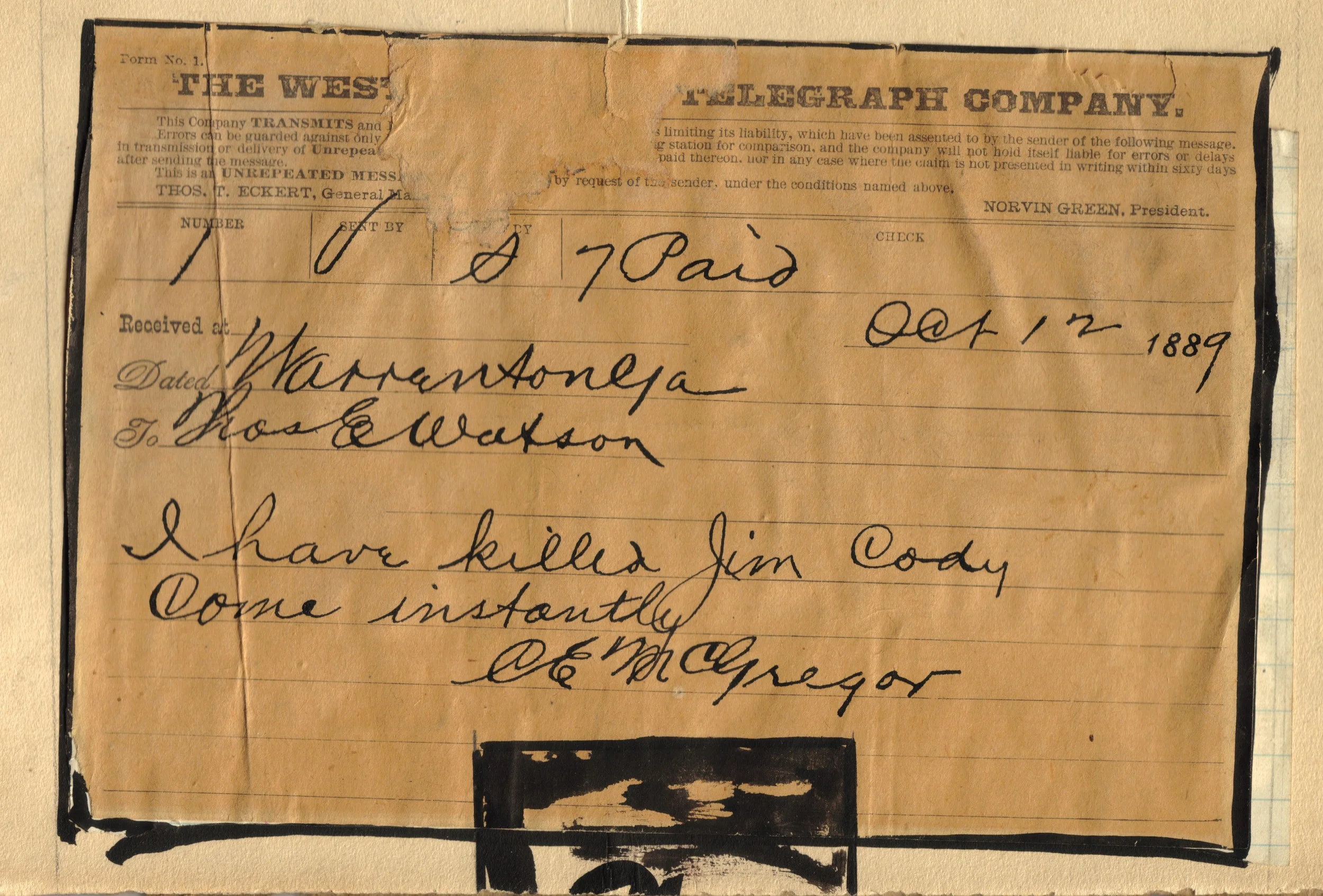

On October 12, 1889, Watson received a telegram from his closest friend, Major Charles McGregor, which read dramatically: “I have killed Jim Cody. Come instantly.”

Charles McGregor, former officer in the Confederate army, was a prominent citizen of Warrenton who had served in the state legislature with Watson. His close friendship with Watson was supported by mutual populist political sentiment.

The feud between McGregor and Cody stemmed from their mutual interest in Mrs. DuBose, a wealthy Warrenton widow. Cody was her cousin; McGregor was married. Town gossip ultimately unnerved Cody and on the night of December 17, 1887, he shot McGregor from ambush in his own front yard. McGregor survived the chest wound. At length Cody admitted he had been the assailant. McGregor did not press for criminal prosecution, but routinely armed himself as he went around town. Cody in the meantime moved to Gainesville, Georgia. He was not indicted for attempted murder until spring 1889. Cody was absent from the first term of Superior Court, and bailiffs failed to locate him.

On Saturday, October 12, 1889, Jim Cody rode into Warrenton, stepped out of his buggy and spoke with a citizen on the street. Charles McGregor approached Cody, drew his pistol and deliberately shot Cody three times: in the chest, the head and the neck. Cody died in the street--any of the three shots would have been fatal. McGregor then wired Watson and walked home. The Warren County sheriff promptly arrested McGregor for murder. Cody had been unarmed.

The McGregor trial began April 10, 1890 and received significant press attention, including the Atlanta papers. Solicitor General William M. Howard represented the state, and was assisted by five special prosecutors hired by the Cody family. The team included Hal Lewis, a preeminent litigator, and Judge H.D.D. Twiggs, a distinguished Savannah jurist known for his sarcasm and great oratorical ability. McGregor was represented by 33 year old Tom Watson.

In less than two days, the prosecution presented its case. The facts were undisputed. In defense, Watson offered no testimony and presented only McGregor’s unsworn statement. Watson’s summation rested the entire case his theory of anticipated self-defense: that to anticipate an assassination by killing the intended assassin first was the logical extension of the law of self-defense.

After presenting his argument to the jury, Watson had McGregor’s wife and children, each wearing mourning attire, ushered into the courtroom and seated next to the defendant. Watson appealed:

This, gentlemen, is the picture you make if you bring in a verdict of guilty. Let me present another picture of the glad sunshine of tomorrow. The holy Sabbath smiles in holy joy through the evergreen trees and falls upon a happy family reunited in yonder household. Charley McGregor, the gold of his soul purified by a fire through which it has gone, stands once more within his own home a free man…That picture you can make by bringing in a verdict of not guilty.

The jury acquitted McGregor after 106 hours of deliberation.

Zeigler Case, Sylvania, Georgia, 1896

Sol Zeigler

George Zeigler, prominent Screven County farmer, boarded a train bound for Sylvania in September 1894 and was seated next to Screven County Sheriff L. B. Brooker. Enraged by a series of disparaging remarks about Populists by George Bellinger, a black Democrat, Zeigler drew his pistol. Brooker responded by attempting to disarm Zeigler, and in the ensuing scuffle was pistol–whipped. Zeigler was disarmed. He disembarked at the next station, where his son, Solomon Zeigler, was waiting.

After father and son were united on the train platform, a verbal altercation began anew with the sheriff. Brooker, still on the train, drew his revolver and shot through the window, striking the unarmed Zeigler in the chest. Sol Zeigler produced his own pistol and rushed into the train. In the resulting shootout, Brooker was shot in the head and side and Zeigler was wounded in the arm. Although seriously wounded himself, George Zeigler attempted to reboard the train but was apprehended by the county coroner, who cut his throat. Ultimately troops were called out to curb the violence. George Zeigler died three days later. Sol Zeigler and Sheriff Brooker recovered from their wounds.

Sol Zeigler swore out a murder warrant against Sheriff Brooker. The grand jury refused to indict Brooker for murder, but did hand down a true bill for assault and battery. Both Brooker and Zeigler vowed revenge and the sheriff harried the Zeigler family for months. Meanwhile, Sol Zeigler and William Walter shot George Bellinger to death. Watson defended Sol and ultimately both he and Walter were acquitted of that murder.

On October 13, 1895, Sol Zeigler and his brother Corrie went to a large meeting at the Goloid Baptist church, where they found Sheriff Brooker in attendance. When Brooker headed for his buggy, the brothers shot him in the back of the head. They then stood over the body, shot it twice more, and drove away. Nearly 200 people saw the shooting. Despite the amount of witnesses, little effort was made to apprehend the assailants until a $1,000 reward was offered and private detectives were employed. On May 25, 1896, the Zeigler brothers quietly surrendered to Sheriff William Patrick and were jailed.

While the brothers were incarcerated, a private detective and a witness to sheriff Brooker’s murder attempted to arrest a Zeigler cousin for seducing a girl years earlier. The women of the house resisted the intrusion. When the cousins returned home, a gunfight ensued. Jake Zeigler was mortally wounded. Lonny Zeigler was wounded and later lost his arm.

The state separated its cases against the Zeigler brothers, and both Sol and Carrie hired Tom Watson to defend them. The trials began November 18, 1896. Attorneys G.M.W. Williams, W.L. Mathews, D.H. Clark, and H.S. White assisted Watson for the defense. Watson’s formidable courtroom adversary, H.D.D. Twiggs, assisted Solicitor–General E.K. Overstreet.

As in the McGregor case, Watson offered only the defendants’ statements as evidence. He again argued his point of anticipation; that a man did not have to wait until his adversary was immediately upon him before he took steps to save his life, and that those steps included killing the adversary. When Brooker headed for his buggy, Watson argued, the Zeiglers reasonably concluded he went there to procure a gun.

Both trials lasted two weeks. Both Zeiglers were acquitted.

Lichtenstein Case, Swainsboro, Georgia, 1900

Sigmund Lichtenstein was a shopkeeper in Adrian, Georgia, a small town in located 75 miles northwest of Savannah. On Saturday, November 10, 1900, local carpenter named John Welch burst into Lichtenstein’s store, demanding a refund on cloth and shoes for his children he had purchased earlier in the week with his poker winnings. Lichtenstein accepted the shoes, but upon examination refused to take back the wrinkled material, explaining that Welch’s wife apparently had begun to cut a dress pattern from it. Welch then asked Lichtenstein to return the money he had paid on his store account. When Lichtenstein refused, Welch flew into a rage and warned that no Jew would spend his poker earnings while his family went hungry. Welch stormed out of the store.

When Lichtenstein left his store later in the day, walking down the street cleaning his nails with a penknife, Welsh staggered from an alley and accosted him. Badly drunk, Welsh cussed and slapped Lichtenstein. The two grappled, Welsh threw Lichtenstein on the ground, drew a pistol and shot him in the leg. He then turned, ran a few yards and fell dead. During the initial fight Welch’s heart had been punctured by Lichtenstein’s pocketknife.

While Lichtenstein recovered from his bullet wound, Adrian Mayor Wilbur Curry, first cousin to Welsh, agitated the local citizenry with anti–Semitic rhetoric and innuendo. Lichtenstein was charged with murder.

Lichtenstein’s wife, Dora, contacted family friend Judge Roger Gamble of Louisville, who accepted the case for free and secured a series of minor legal successes. As the trial neared, and Mayor Curry continued to disrupt an otherwise sympathetic atmosphere, Gamble urged the family to hire Tom Watson, a “man of the people.” Lichtenstein was indicted for murder in the April term of Emanuel Commission Superior Court. At Watson’s instruction, Gamble managed to have the trial scheduled at the end of the court’s term, when the jury would be impatient for its term to end and uncomfortable from the summer heat. Watson also instructed the family on their courtroom appearance and behavior. The trial was scheduled for July 10, 1901.

Judge Gamble conducted the trial for the defense. Watson took no notes, but simply closed his eyes and listened to the testimony. His apparent and inactivity exasperated Lichtenstein’s family, who urged Gamble to make his co–counsel do something “lawyerly.” Watson overheard the comments and simply smiled.

When Watson began his summation, it was clear that he had listened to every detail of the testimony. His summation began: “You all know who I am and that I am one of you. I am not going to tell you anything that’s not true.”

The courtroom erupted from the thrilling performance because of his ability to marshal facts. The family realized he had listened to all testimony.

All but one juror quickly voted for acquittal, one held out arguing that if the county was going to waste his time trying a man Watson spoke for, then he would get a meal out of it. After noon supper, the Jury returned a verdict of not guilty.